(June Millicent Jordan)

born July 9, 1936 in Harlem, New York City

died June 14, 2002 in Berkeley, California

American poet, essayist, teacher, and activist

90. birthday on July 9th, 2026

Biography • Literature & Sources

Biography

“As a black woman, as a black feminist, I exist, simultaneously as a part of the powerless and as a part of the majority peoples of the world.”

It seems particularly important to honour black American poet and activist, June Jordan, because of her deep association with the people of Palestine. Jordan saw the fate of Black people linked eternally to the fate of Palestinians: “two peoples facing the same empire.” She described the Palestinian struggle as “the moral litmus test” of her life: “I am born a Black woman, and now / I am become a Palestinian.”

Her fellow activist Angela Davis wrote:

When, long ago, she stood up in support of the Palestinians, June was banished from many circles. But she continued with her remarkable courage and her capacity to choose the words that summon people to produce profound insights about their own responsibility to make a better world.

Another friend, Alice Walker, who wrote The Color Purple, and who herself courageously joined the Freedom Flotilla to Gaza in 2011, described Jordan as “courageous, rebellious and compassionate ... an inhabitant of the entire universe. She makes us think of Akhmatova, of Neruda. She is the bravest of us, the most outraged. She feels for all. She is the universal poet.” And for novelist Toni Morrison, June Jordan's career was: “Forty years of tireless activism coupled with and fuelled by flawless art…All that aside, she was a joy to know.”

Resistance poets across the world have felt a strong identification with Palestine. South African poet, Breyten Breytenbach, wanted all poets to declare themselves “honorary Palestinians,” and Seamus Heaney linked Ireland and Palestine in his Nobel Prize lecture. June Jordan visited Lebanon and Palestine and spoke out about the 1982 massacres in Sabra and Shatila during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. Already then she could acknowledge her own complicity as a US tax-payer and, writing of her visit, she said: “Yes I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that/ paid/ for the bombs and the planes and the tanks/ that they used to massacre your family. . . I’m sorry. I really am sorry.” (1985, 106).

She died of cancer age 65 in 2002 and did not live to see the genocide today, but her 2005 poem, “Moving Towards Home,” could have been written now:

…because I do not wish to speak about unspeakable events

that must follow from those who dare

“to purify” a people

those who dare

“to exterminate” a people

those who dare

to describe human beings as “beasts with two legs”

those who dare

“to mop up”

“to tighten the noose”

“to step up the military pressure”

“to ring around” civilian streets with tanks

those who dare

to close the universities

to abolish the press

to kill the elected representatives

of the people who refuse to be purified

those are the ones from whom we must redeem

the words of our beginning…[Essential June Jordan p. 93]

The editors of the 2021 Essential June Jordan were struck by how many times they said “this could have been written now! That’s the art and urgency of this extraordinary poet, activist, thinker, lover, fighter, and teacher who took up the daunting task of telling us who she was and, more importantly, who we are.”

June Jordan was born on July 9, 1936 in Harlem, New York, to Jamaican immigrants, Granville and Mildred Jordan. She wrote her first poems by the age of seven, many of them about a difficult childhood with an abusive father who beat her for not being the boy he wanted. She went to an all-white prep school in Massachusetts and then to Barnard College. In 1955 she married Michael Meyer, who was white, and had a son, Christopher. Soon after they divorced in 1965 her mother committed suicide. At this point she began her long teaching career.

She taught at Yale and Wisconsin, SUNY and CUNY and ultimately in the African American Studies Department at UC Berkeley, where she was full professor of English, Women's Studies, and African American Studies, from 1989 to 2002, and founded her “Poetry for the People” program, aimed to inspire and empower students to use poetry as a means of artistic expression. She also championed the use of Black English in the education system, working with her students to see the structure that exists within Black English, and respect it as its own language rather than a broken version of another language. In Berkeley, there is a mural in her memory:

In the painting she looks to her right — toward the future — fixing her gaze on the Palestinian flag. The painter of the mural has placed a Black power fist to Jordan’s left, with a keffiyeh around her shoulders. The ending declaration of her poem, “Moving Towards Home”: “and now I am become Palestinian,” is printed along the scarf’s edges.

Her first book, Who Look at Me, was a children’s book, published in 1969. She won a Rome Prize and a Rockefeller Grant in 1970. Her first collection of poems was edited by Toni Morrison in 1977, and that same year Leonard Bernstein set her words to music. As a bi-sexual, she was the first African American woman to publish a book of love poems, Haruko/Love Poems (1994). She was prolific and versatile, believing that being free meant the freedom to be unpredictable, whether about her own sexuality or about the causes she espoused. She could as easily pen a regular column for the Progressive magazine as collaborate with John Adams and Peter Sellars on the 1995 opera, I Was Looking at the Ceiling And Then I Saw The Sky. She said:

The composer, John [Adams], said he needed to have the whole libretto before he could begin, so I just sat down.…and wrote it in six weeks, I mean, that's all I did. I didn't do laundry, anything. I put myself into it 100 percent.

After the Harlem Riots of 1964, Jordan was “filled with hatred for everything and everyone white.” She collaborated with architect R. Buckminster Fuller on a redesign of Harlem to provide a better environment for the residents, but their proposal was not implemented. In her 1974 Poem about Police Violence she asks, “What you think would happen if/ every time that they killed a black boy, then we killed a cop.” A searing question that cuts to the heart of racism and power and state violence.

Jordan excelled as a political essayist. Her collection Civil Wars (1981) was the first such work to be published by a black woman. In subsequent volumes, including On Call (1985) and Technical Difficulties (1992), she wrote about South Africa, Nicaragua and Lebanon, as well as aspects of race and class in the US.

Jordan's 1971 novel, His Own Where, and her 2000 memoir, Soldier: A Poet's Childhood, portray her family situation. Her relationship with her father, a postal clerk, was turbulent, but he passed on to her a love of literature, from the Bible to Shakespeare, Edgar Allan Poe and Paul Laurence Dunbar. He encouraged her to memorize passages of classical texts but would beat her for the slightest misstep and call her “damn black devil child.” Her self-sacrificing mother tragically committed suicide. In a moving essay, “Many Rivers To Cross,” Jordan wrote: “I thought about the idea of my mother as a good woman and I rejected that, because I don't see why it's a good thing when you give up, or when you cooperate with those who hate you or when you polish and iron and mend and endlessly mollify for the sake of the people who love the way that you kill yourself day by day silently… I am working for the courage to admit the truth that Bertolt Brecht has written; he says, 'It takes courage to say that the good were defeated not because they were good, but because they were weak.'”

The years when she was struggling as a single mother were her formative years as a writer. As a self-avowed anarchist activist, her poetic ambition was to be a “black people’s poet” in the fashion of Pablo Neruda. Her poetry alludes to events such as the 1991 Clarence Thomas/ Anita Hill hearings, Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign, and the 1991 police beating of Rodney King. She wrote personal poems about being raped and coping with illness. These express anger but also sympathy for all sufferers of injustice and violence: lesbians and gays, victims of police brutality, or the people of sub-Saharan Africa, Nicaragua, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Palestine.

In June 2019, Jordan was one of the inaugural fifty American “pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes” inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument in New York City.

In “A Poem About My Rights,” written after she was raped, she urges victims of violence to resist the temptation to internalize the blame for the violent act and put it squarely on the shoulders of the perpetrators. She moves from her personal tragedy to the situation of violated people everywhere: “I am the history of rape/ I am the history of the rejection of who I am.” The difference between her rape and the situation in apartheid South Africa, for example, was minimal. Her anger at this violation finds expression in the menacing final lines of the poem: “but I can tell you that from now on my resistance/ my simple and daily and nightly self-determination/ may very well cost you your life.” Her poems are love poems to the oppressed and marginalized.

Her final collection, written during her battle with breast cancer, is more optimistic and conciliatory, dedicated to an anonymous lover, and to the “Student Poet Revolutionaries” in her “Poetry for the People” project at Berkeley. She criticizes America’s bombing of Iraq, the Israeli devastation of Lebanon, and the anti-abortion movement, but the poems are introspective and accepting.

After her death, Angela Davis gave this tribute: [July 15, 2002]

No one who had the privilege of knowing June Jordan—a poet reading her work, a political agitator delivering a speech full of rage, a teacher conveying the passion and import of poetry, a friend talking about whatever—could escape the seductive, high-pitched laughter that always punctuated her conversation. There was joy in everything June undertook. I would call her sometimes for no other reason than to feel the exhilaration of her protracted laughter. Her lifelong devotion to justice, equality and radical democracy seemed to revolve around the pleasure she felt in hurling beautiful words at a world full of racism, poverty, homophobia and inane politicians determined to preserve this awful state of affairs. There was always joy in her rage. Politics was her life; collective pain, as well as collective resistance, was always something she felt in a deeply personal way. June is often characterized as an activist. Many of those who were troubled by her insistent coupling of poetry and politics used the word “activist” to discredit her. What, they asked, did the mundane world of politics have to do with poetry? On the other side, there were activists, who wanted to know how poetry could possibly change the world. June was a magnificent poet and a powerful activist. She changed people's worlds with her words and she created beauty in the process.

Author: Mary Adams

Literature & Sources

Jordan, J. (1985). Living Room: New Poems, 1980-1984 (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press)

Kinloch, V. (2006). June Jordan. Her Life and Letters, Praeger Publishers, Westport, Ct

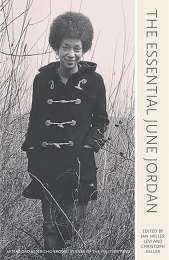

The Essential June Jordan. 2021. Eds. Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller. Afterword by Jericho Brown. Penguin Modern Classics.

https://www.junejordan.net/

https://www.enotes.com/topics/june-jordan/critical-essays

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.