(honorary name: Jianhu Nüxia (鑑湖女俠) = Knight of Mirror Lake )

born on November 8, 1875, in Xiamen (Fujian Province), China

died on July 15, 1907, in Shaoxing (Zhejiang Province), China

Chinese women's rights activist, writer, martial artist, and revolutionary

150th birthday on November 8, 2025

Biography

If Qiu Jin had been European or American, she would have been at least as famous as her contemporaries Hedwig Dohm, Anita Augspurg, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, or Alice Paul. Her demands were by no means less radical than those of her Western sisters, nor was her personal commitment any less self-sacrificing – quite the contrary, as she paid with her life. Qiu Jin fought two battles: on the one hand, for the liberation of women from male subjugation, and on the other, for the liberation of her country from the Qing dynasty and the foreign powers that behaved like colonial rulers in China.

No woman of the late Chinese imperial era left a more indelible mark on the history of her country. Alongside Sun Yat-sen, she is the only historical figure still honored today in both China and Taiwan. On the 50th anniversary of her death, a museum was inaugurated in her hometown of Shaoxing. Since her violent death, several dozen monographs and countless articles have been published about her. In 2005, a stamp bearing her image was issued in China. Monuments have been erected in her honor. Her life has been filmed four times (most recently in 2011), both in China and Hong Kong as well as in Taiwan.

Nevertheless, Qiu Jin is virtually unknown in the Western world, even in feminist circles. This is in part due to the fact that there is very little literature about her available in Western languages. Of her own literary works, which include both poetry and prose, only her unfinished magnum opus, the novel The Stones of the Bird Jingwei, and a few poems in French, German, or English are available. But a certain Western arrogance and disregard for personalities from “exotic” countries could be an additional reason for her relative invisibility.

Qiu Jin was born into a well-to-do and educated family of civil servants in Xiamen. Originally from Shaoxing, the family moved with her grandfather to Xiamen when he was appointed city prefect there. As Xiamen had been a British treaty port since 1842, her grandfather regularly dealt with Englishmen; he was subjected repeatedly to humiliations that the young Qiu Jin also became aware of. Embittered by his treatment, he resigned from his post in 1890 and the family then returned to Shaoxing.

Qiu Jin was the second of four children: she had an older brother, a younger sister, and a younger brother. Her upbringing was unconventional by the standards of the time: she was educated, although schooling was not yet compulsory and education was usually at best reserved for sons. Daughters were generally considered of little value, as only a son could pray to the ancestors and bring prosperity and prestige to the family. A girl cost money to raise and a dowry had to be provided, and as a bride no more than a modest sum would be paid to the family when her marriage was arranged. After the wedding, the couple would live with the husband's family; the daughter was of no further use to her parents.

But Qiu Jin’s mother, Dantai, was an educated, cultured woman who taught her daughter to read and write and instilled in her a love of literature and poetry. At the age of eleven, Qiu Jin was reading the classical poets and began to write her own verses. She picked up further knowledge when her older brother took lessons with a tutor. Qiu Jin acquired practical skills as well: her maternal uncle and her cousin, a grand master of martial arts, taught her horse riding, body control, and various martial arts, including stick and sword fighting.

These activities suggest that Qiu Jin's feet were not bound, as was common practice at the time. Foot-binding had been practiced in China since around the 10th century. Feet that were as small as possible were considered the ideal of beauty and sexually attractive to men. Men in higher positions in particular liked to boast about their wives' tiny feet, since this meant that it was not necessary for the wives to work as there were servants. Bound feet also had the “advantage” of significantly restricting women's range of movement. Apart from the unnatural posture and the unspeakable pain caused by inflammation, dying toes, and rotting flesh, many women could only walk by balancing in high-heeled shoes and holding on to walls. The deformation of girls' feet began at the age of six, when their toes were bent backward and bound ever tighter. Mothers in particular attached great importance to this custom, as it increased their daughters' marriage value. Only in the lower classes were feet bound less or sometimes not at all, because here men could not afford to have women just sitting around.

The great gratitude that Qiu Jin felt towards her mother throughout her life was probably also due to the fact that her mother had not insisted on this tradition being observed.

In 1896, at the relatively late age of 21, Qiu Jin was married in the usual manner: the two fathers agreed on her marriage to Wang Tingjung, the son of a merchant and estate manager from Hunan province. Like him, his family was very conservative and tradition-conscious. Qiu Jin described him as “nouveau riche, unscrupulous, and uneducated.” She felt lonely and with no one to talk to, she began expressing all her thoughts and feelings in poems and short prose texts. It was only when she gave birth to her son Yuande in 1897 and her daughter Guifeng in 1901 that her parents-in-law were satisfied.

In the years that followed, Qiu Jin became highly politicized due to the developments in China. Beginning in 1898, a reform movement had sought to transform the country into a constitutional monarchy with a national parliament and to modernize the state through reforms in agriculture, industry, trade, and education. The movement had failed, primarily due to resistance from Empress Cixi. In the opinion of numerous intellectuals, this showed that real reforms were not possible without first overthrowing the Qing dynasty. State repression, corruption, famine, banditry, mass discontent, and agitation by various secret societies led to the Boxer Uprising in 1900. Foreign powers – primarily Great Britain, France, the German Empire, Russia, Japan, and the United States – saw their privileges in danger and sent an expeditionary force to crush the uprising, thereby ultimately supporting the weak imperial regime.

It proved to be a stroke of luck for Qiu Jin that her husband bought a position in the Ministry of Finance and Taxation in Beijing in 1900 and the young family moved to the capital. She enjoyed greater freedom as a woman and met reform-minded intellectuals. Wu Zhiyin, the equally progressive wife of one of her husband's colleagues, became her first close friend. Together with other women, including the Japanese wife of another colleague, they discussed the situation of Chinese women and agreed that urgent action was needed:

According to Confucian teachings, women are fundamentally subordinate to men. Not only were girls in China denied educational opportunities and valued mainly as brides, they were subordinate to men throughout their lives: first to their fathers, then to their husbands, and finally to their sons. Their assets, if they had any, became the property of their husbands. The husband could take a concubine or divorce his wife, but the wife couldn’t. If the husband died, the wife was required to mourn for three years and was not allowed to remarry. A widower, in contrast, was permitted to look for a “replacement” immediately after his wife was buried. Qiu Jin realized how urgent the problem of widows was given the fate of her own mother: when her father died in 1901, her father’s family refused to support the “mother-in-law” financially. Throughout their lives, women were completely dependent on men, not least because their bound feet made it impossible for them to make their own way through life.

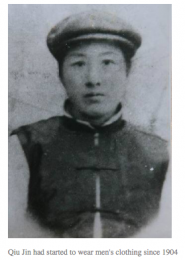

Qiu Jin learned that the living conditions and educational opportunities for women were far better in Japan. It was not unusual for Japanese women to study. Many Western works had been translated into Japanese. Indeed, the concepts of emancipation and of revolution came from Japan. For the Chinese, Japan was a haven of progress. In 1904, Qiu Jin spontaneously decided to leave her husband and children and to travel to Tokyo. Before doing so, she had Wu Zhiyin sell her jewelry so that she had enough money for travel and study.

In Tokyo, Qiu Jin was immediately surrounded by like-minded people; this was where her political career began. She learned Japanese, passed the entrance exam to a women's college, attended lectures, and joined several Chinese student societies, including the revolutionary-oriented Tongmenghui, founded by Sun Yat-sen, who was also living in Japan. She founded the all-female Gongaihui and joined the secret society of the Triads. The Gongaihui's statutes stipulated that women be trained to take on national responsibility. In the conflict between reformists (who wanted to maintain a constitutional monarchy in China) and revolutionaries (for whom the deposition of the Qing and the proclamation of a republic were the conditions for a new beginning), Qiu Jin sided with the revolutionaries. She met her distant cousin Xu Xilin, with whom she would later lead the uprising in the provinces of Zhejiang and Anhui.

She soon became known as a talented and inspiring speaker and began writing articles on a wide range of topics for student newspapers published by Chinese women. She began working on The Stones of the Bird Jingwei, a novel written in the form of a classical tancis, a type of chanting mainly practiced by women for women. Through the two protagonists, Jurui and Shaoxi, she promoted women’s friendships with women, women's education, and women’s independence from men.

In her speeches, poems, and articles, Qiu Jin advocated for education and training for all girls—regardless of their social class—not only in the arts, but also in physics, chemistry, and astronomy, so that they could live independently of men. She also fought for the prohibition of foot-binding and bride buying. For Qiu Jin, women and men were equal in their rights and duties. This also included the duty to take up arms, which she believed was absolutely necessary to overthrow the Qing dynasty and drive foreigners out of the country so that a democratic republic could be established and political, social, and economic reforms implemented. These reforms, in turn, were necessary to secure equal rights for women. She signed her articles with Jianhu Nüxia (Knight of Mirror Lake). She searched for role models in literature and found them in Joan of Arc, the French revolutionary Jeanne-Marie Roland, and the Russian anarchist Sofija Perovskaia – and she took lessons in shooting and explosives manufacturing.

Qiu Jin returned to China in early 1906. In the north of Zhejiang province, she initially taught Japanese and sports at one of the gradually increasing number of girls' schools. She called for the introduction of science subjects and further foreign languages at girls' schools. She encouraged girls to pursue higher education and a career in order to be financially independent. A scandal in conservative Chinese society!

But that was not enough for her: she founded the first Chinese women's magazine, Zhongguo nübao (Chinese Women's Magazine), in which she called on women to no longer accept oppression within their families and society and, in particular, to resist foot-binding and arranged marriages. However, the magazine had to be discontinued after only a few issues due to a lack of money.

Qiu Jin realized that social reforms would only be possible after a change in the political balance of power. She accepted the offer from the Guangfuhui, one of the largest armed revolutionary organizations, to become headmistress of the Datong School in her hometown of Shaoxing. One of the Guangfuhui’s cells was led by Xu Xilin, the founder of the Datong School. On the surface, Datong appeared to be a normal school, but it secretly served as a place for recruiting and training revolutionaries. Qiu Jin was held in high esteem by her students. She taught martial arts and tried to attract more women to the school. She had a reputation in the city for being honest and honorable and for standing up for the poor and weak. The Guangfuhui assigned her and Xu Xilin the task of leading the revolution in the provinces of Zhejiang and Anhui, making Qiu Jin the only high-ranking woman in the revolutionary movement. This provoked envy, with some believing she was not up to the task; her adversaries were further angered that she dressed as a man in black garments and galloped fearlessly through the streets on her horse at full speed.

However, the uprising that had been planned for July 19, 1907 failed. The plans were betrayed and premature unrest in early July had alerted the armed forces. Xu Xilin, who was to have led a diversionary maneuver in Anhui, tried to salvage what he could by killing the governor of Anhui province on July 6; he was captured and executed shortly thereafter. Government troops then marched towards Shaoxing. Qiu Jin, warned by a student at the military academy, hid all weapons, burned incriminating material and the lists of students' names, and sent the students home. When Datong was surrounded on July 13, she was there alone with another teacher and five students.

Qiu Jin was then taken to the women's prison in Shaoxing, but she refused to talk and nothing incriminating was found. She was tortured to force her to reveal further plans and the names of her co-conspirators; despite the abuse, she remained silent. Although she could not be personally accused of anything, she was sentenced to death by sword and beheaded two days later. She was not even 32 years old.

Before her execution, she had expressed three wishes: she wanted to write to her friends; she did not want to have to undress before her execution; and she did not want her head to be shown to the crowd afterwards. The last two wishes were granted.

The Chinese Revolution that brought down the empire took place in 1911. Sun Yat-sen, the first president of the Republic of China from 1912, honored Qiu Jin as “the first martyr” of the revolution and had a memorial plaque erected in her honor. After overcoming numerous difficulties, Qiu Jin's friends Wu Zhiyin and Xu Zihua finally succeeded in 1912 in transferring her coffin to West Lake near Hangzhou, as Qiu Jin had wished, and erecting a mausoleum.

The women's movement which began emerging in China starting in 1912 was strongly influenced by women's rights activists in Europe and the United States – yet the Chinese activists also honored Qiu Jin’s contributions by referring to her as “China's first feminist.” Guifeng followed in her mother's footsteps in her own way: she became China’s first woman pilot.

(Text from 2016; translated with DeepL.com; edited by Ramona Fararo, 2025.

Please consult the German version for additional information, pictures, sources, videos, and bibliography.)

Author: Christine Schmidt

Quotes

Furthermore, a terrible custom had been widespread for thousands of years: men were overvalued and women were undervalued. The men in that country had written entire books and invented barbaric rites specifically to enslave women. They had practiced cruel mechanisms of oppression. In order to be able to unabashedly make evil use of it, they had found the following formula: for a woman, a lack of intellectual gifts is a virtue. Thus, women were not educated and remained in complete ignorance. Once men had begun to exaggerate their own merits, they ultimately regarded women as their slaves, as beasts of burden. They knew nothing of the fact that men and women are equal by nature. That they are beings with four limbs and five senses, with wisdom and intelligence, courage and strength, and they also did not know that women have the same rights and duties as men. [from: The Stones of the Bird Jingwei]

With all my heart I beseech and beg my two hundred million female compatriots

to assume their responsibility as citizens. Arise! Arise! Chinese women, arise!

If those [women] who are rich and happy were to show generosity, they could use their money or influence to help other women by ensuring that schools and factories are opened for them. Then these women could study, learn a trade, and thus work for their own livelihood and finally stop enduring this misery.

Praying all day long is useless; at best, it keeps you stuck in misfortune and hardship forever. Demons, immortals, evil spirits, Buddha—these are all lies to mislead people. [...] Let me ask you something: have you ever experienced a disaster, a flood, a looting, a war, and seen demons, immortals, or Buddha come to your aid?

How happy we would be if all of us, men and women alike, could emulate our ancestors, who were equally skilled in political and military affairs. Then it would be easy for us to drive out the foreigners, and we could easily restore the country's prosperity. Then we would not be where we are today: resigned to death, defenseless and at the mercy of a government that oppresses us within the country and delivers us to foreign powers that set their armies upon us.

There are men who were constantly supported by their wives during their difficult studies. The wives endured poverty and hardship alongside them, and on the day when these men finally achieve their goals, they take a pretty concubine or mistress and chase their first wife away, never remembering the support they had received from her.

Why should men be honored, but women not even count? For example, women have no right to a share of the wealth; the entire inheritance goes to the sons. A daughter is just as much a descendant of her parents as a son, so why should there be double standards when it comes to distributing the inheritance?

What could be more ridiculous than marrying two people together just because their horoscopes match?

Bound feet have always been something shameful. Women torture their own bodies to get small feet! They cannot move freely when walking because the crushed bones and atrophied muscles hurt so much. [...] In dangerous situations, they are as helpless as prisoners because they cannot flee since they cannot move. [...] There are also women who have no self-respect whatsoever. They love their small feet as much as their husbands do; they tie the bandages that hold them together ever tighter and can thus flatter themselves that they have succeeded in making their feet resemble a three-inch lotus bud. [...] When they have to lean against their door, they consider themselves beautiful and attractive. Instead of fighting against their living conditions, they are content with themselves and are satisfied with being slaves to their sons and husbands. But don't they know that it is a habit of men to abandon their old wives and take a new wife? Do they believe that their husbands will not leave them because they have small feet? [...]

It is truly not worth forgoing the well-being that one enjoys with unbound feet. For if one does not bind one's feet, one never has to grimace in pain when walking, even on difficult paths. You become strong because you can do sports, and the weakness and frail beauty of the past are gone. You can devote yourself to all kinds of activities and no longer need the help of a man.

Women must learn something in order to become independent. They must not always cling to men in everything.

The young intellectuals are all chanting, ‘Revolution, Revolution,’ but I say the revolution will have to start in our homes, by achieving equal rights for women.

Don't say that women can't be heroes. They ride on the wind 10,000 li far to the east.

Who would have thought that it [= a sword] would end up in my hand?

The sword in my right hand, the liquor in my left,

drunk and exuberant, I raise it while dancing.

It swings through the air like dragons and snakes.

How could I become a slave to the Hu [= Manchu] begging for rice?

[from: Jian ge, the sword song]

May heaven grant men and women equal power.

Is it pleasant to live lower than cattle?

We will rise in flight, yes.

We will spiral upward.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.