(Germaine Louise Krull)

born on November 29, 1897 in Wilda near Poznan, the German Empire (now Poland)

died on July 31, 1985 in Wetzlar, West Germany

German-Dutch photographer, war correspondent and hotel manager

40th anniversary of her death on July 31, 2025

Biography

She called herself “chien-fou” (French for “crazy dog”). In the eyes of a society eager for glimpses into the supposedly scandalous lives of its women artists, she seemed the ‘perfect’ artist. Not only was she audacious enough to start afresh a total of seven times, but she generously shared details from her life – as well as numerous entertaining anecdotes – in four autobiographies (1). The illustrious life of Germaine Krull also provided the material for a play produced for radio as well as for a 160-page novel (2).

Her non-conformist photographs delighted a host of avant-garde art scholars. The photo historian Herbert Molderings believes that it was Krull who actually founded photographic modernism in France in 1928 with her portfolio Métal. She took up socialist and anarchist causes several times and lived in Europe, Africa and Asia. In apparent accordance with the widespread cliché of modernist artists and their internationalist and left-wing leanings, she rejected narrow-minded conventions and restrictions. She especially abhorred those of the dual gender order, gleefully pointing out that she had already worn boy's clothing as a girl. She changed her political camp at least three times. Yet as an internationalist she failed miserably: like Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse, her view of the world beyond Europe would remain disparaging and colonialist throughout her life.

“Like a mirror that transforms the image of the world”: First steps

Jean Cocteau, the multitalented French artist, was deeply impressed by Krull's photographic talent, writing in 1930 that she was like a “mirror that transforms the image of the world.” Yet Krull had only become a photographer by chance. Forced by her mother, a sometimes-aloof Munich boarding house owner, to undergo an abortion at the age of 18, the only remaining emotional tie and sense of obligation she felt was towards her younger sister Berthe, who was nine. She had long since written off their father, an engineer and free-thinking bon vivant who had deserted the family in 1912.

A year after the outbreak of the First World War, Krull planned to start a life of her own and to study at university. Lacking a high school diploma, she had to enroll at the Munich School of Photography instead and thus began attending school regularly for the first time in her life. The family had moved countless times; throughout a childhood spent in Bosnia, Italy, France, and Switzerland, she had been homeschooled by her father. Although he bequeathed to her a “strong legacy of freedom,” he left her with “no knowledge.” She lamented that she “read like a four-year-old child” and was ashamed of her poor grammar her entire life.

“The little fairy was not yet the queen”: Schwabing and Moscow

Krull was only 21 years old when she opened her first studio in Munich-Schwabing, a stronghold of left-wing and right-wing artists. Franziska zu Reventlow, Ricarda Huch, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas and Katia Mann lived and worked there. Krull initially remained committed to the so-called pictorialism that had been presented to her as the ultimate in contemporary photography during her training. Through its orientation towards the painting of days gone by, it promised a hint of ennoblement at a time when photography was denied any artistic quality. Krull's use of light in some of her early portraits recalls Rembrandt's likenesses.

Krull was ambitious and determined to play a leading role in the art world. She wanted to be the “queen,” to turn the studio into “a kind of meeting place for all of Schwabing.” However, she was arrested following her active involvement in the November Revolution and forced to close the studio in 1919. After she was expelled from the country in 1921, she went to Russia with an activist who was her partner at the time, the Ukrainian Samuel Levit. Declaring herself an anarchist, she rejected the major communist parties of Europe as dogmatic and authoritarian and was accused of espionage. She was arrested as a counter-revolutionary and almost executed. In January 1922, she fell ill with typhus and was expelled from Russia.

“Champagne and Madness”: Berlin

Freshly recovered and with the active support of her close friend Max Horkheimer, Krull moved to Berlin in 1922. Far removed from the harsh reality of a city suffering under rampant inflation, she described her life in Berlin as a lavish party: “Everything was available, money had no value. You had to spend it, because the next day it would be worth even less.” She was moved in the literary, art and theater circles, and met Arthur Lehning, George Grosz and Bertolt Brecht. By the time she opened a new studio in 1923/24, she had emancipated herself from pictorialism and was working more objectively. She tried her hand at street photography, developed her nude photography further, fell in love with the Dutch documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens and with a woman whom she refers to in her memoirs only as “Elsa.”

“Everything was made of steel”: Amsterdam

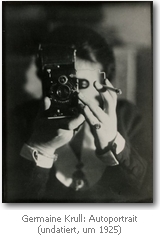

Krull and Ivens moved to Amsterdam in 1925. Their love had long since cooled when she married him in 1927; she simply wanted to obtain the Dutch passport that she was to keep for the rest of her life. Ivens considered Krull his greatest inspiration, writing in his memoirs that “through her I gained access to a world of which I had only fantasies. It was my encounter with art, with life.” Meanwhile, in the port of Rotterdam, Krull marveled at the giant steel cranes, the “forests of iron,” the ocean liners, the world of machines – favorite motifs of the Russian Constructivists, the Bauhaus, and the Dutch De Stijl group. “A great era has dawned” was the enthusiastic pronouncement of the machine-obsessed architect Le Corbusier in his bestselling Vers une architecture (1922). Krull, however, was as equally repelled by the mechanized universe as she was attracted to it; she decided to approach the “metal giants” more closely photographically in order to “perhaps to make them more human.” In retrospect, she viewed this idea, conceived when she was 28, as the birth of her photography. Around the same time, in 1925, she created the famous, surrealistic self-portrait, with which she declared the camera the core of the self.

“Finally, back”: Paris

In 1926, Krull followed her heart and went to Paris, where she had already spent a brief time as a child. The artistic circles of the Rive Gauche, the Café Aux Deux Magots, and Montmartre soon became her lifeblood. However, no one was (as yet) interested in her photos of machines. She earned her living with fashion photography – her friend Sonia Delaunay helped her establish contacts. Like Lee Miller, Krull was desperately unhappy in the genre: “If there was one thing in the world that never appealed to my photographer's eye, it was definitely fashion.” Haute couture photographs at that time were taken exclusively in studios; Krull, like her colleagues Marianne Breslauer, Gisèle Freund, Ilse Bing and Ellen Auerbach, was drawn to the streets.

She later wrote that she threw in the towel when she was expected to use a cramped studio even for photographs of the dancer Josephine Baker. From then on, she strolled along the quays of the Seine with her small camera, an Ikarette Agfa 6 x 9, seeking life on the boulevards and in small alleys. In a series of breakneck stunts, she climbed around on an “old black thing” – the Eiffel Tower – for Vu, the first French weekly illustrated magazine. She wanted to bring the 10,000-tonne monster to life. She was not interested in the long shots typical of postcards with their trite romanticism. She was looking for unusual details, and she used backlighting. It was always the diagonal favored by Neues Sehen (New Vision) that she placed in the foreground. When Krull published her technical impressions in the portfolio Métal in 1927/28, they immediately caused a sensation. Walter Benjamin began to mention Krull in the same breath as the German photographers August Sander and Karl Blossfeldt. She was celebrated in Paris as a master of modern photography, alongside Man Ray and André Kertész, and she was praised as a machine photographer and “iron Valkyrie” (Eugène Merle). Peugeot, Citroën and the Paris electricity company all commissioned her work.

When she wanted to take one of her most famous portraits, of the writer Colette, the latter initially resisted: “You'd be better off photographing your machines.” Krull participated in important international exhibitions, such as Fotografie der Gegenwart (Contemporary Photography) in Essen (1929) and the Werkbund touring exhibition Film und Foto (Film and Photo, 1929). Like Bérénice Abbott, she was increasingly on the road for Vu, published illustrated books, experimented with multiple exposures and collage-like details. She worked on scenes from the Parisian underworld, landscapes, and portrayed André Malraux, Jean Cocteau and S. M. Eisenstein.

“Children of Misfortune”: Pictures of the homeless

“Le beau c'est le laid.” The graphic artist Käthe Kollwitz, who sketched the destitute of society, declared the ugly to be the beautiful. In a diary entry in 1941, Kollwitz confessed that initially “compassion, empathy” had played only a surprisingly small role. The same applied to Krull: when the magazine Vu commissioned her to photograph homeless people between Nôtre Dame and Pont Neuf in 1928, the subject complemented her works perfectly given that she had so often and so gladly photographed the dark side of the big city. The writer Pierre Mac Orlan had poked fun at her, quipping that “the children of misfortune” were rushing up to gather around Krull. Contrary to what one might expect given her childhood, Krull neither harshly criticized society’s indifference to suffering nor did she seek to expose how merciless life was for those who lived in poverty. In contrast, clinging to old “bohemian” myths, she euphemistically called the homeless “clochards.” Much like her colleagues Marianne Breslauer, Brassaï or André Kertész, she reinterpreted homeless people as marginalized soulmates, as “philosophers” who had voluntarily renounced property and commitment in order to “live freely, à la cloche.” It thus seems only logical that she created the Clochards series not for a political pamphlet, but for Vu, a chic weekly. The photographs were embedded in a text written by her friend Henri Danjou, who romanticized poverty and glossed over the grim realities – her reportage read like a tribute to vagabonds with their supposedly carefree, freewheeling lives. Krull captured the spirit of the times and reaped enormous applause. The fact that she had photographed the homeless against their will, as she later admitted, apparently did not interest the social romantics who read Vu.

The “best pictures… I have ever taken”: In the service of Charles de Gaulle

In 1938 Krull wrote to Walter Benjamin that “thousands of dead and so much suffering” would be brought about by Hitler. When the Second World War broke out, her dormant political fighting spirit was awakened. The former anarchist began to work for Charles de Gaulle's government-in-exile, France Libre. She set out from the African France Libre center in Brazzaville in 1942/43 to take photos – in all probability, the only woman to do so – in order to highlight the relevance of French-annexed territories for the war economy. Krull became an active participant in the war propaganda: she censored her own work and withheld images of forced laborers. She was shocked when she came across a sign in a café in Cape Town that proclaimed in large letters “No dogs and blacks allowed.” Later she also criticized the death of thousands of Congolese forced laborers during the construction of the railroad ordered by Europeans. Yet many of her Africa texts and photos reveal a deeply rooted colonial mentality. In one photo, she can be seen raising her camera above a “victim” who helplessly tries to shield himself by holding his arms up above his head. In another, she literally pushes two children with fear-filled eyes up against a wall. Thomas Schirmböck is quite rightly reminded of “the old textbooks on race.” Krull herself, however, regarded some of these shots as “among the best pictures I have ever taken.”

“An amusing experience”: between capitalism and Buddhism

Krull, a fervent Gaullist, felt that Europe in 1945 was politically “not as it could have been.” She set off for Asia, working as a war correspondent in Vietnam. When on vacation in Thailand, she ended up remaining in the country for a total of 20 years. At the age of 49, a “whim of fate” provided her with what she called “an amusing experience”: she became director of a run-down hotel in Bangkok. The former socialist quickly turned Hotel Oriental into one of the most expensive addresses in Asia, becoming one of the country's few influential female managers. Photography had taken a back seat. At the age of 70, she abandoned the hotel business and dared yet again to make a completely fresh start: declaring herself a Buddhist, she moved to North India and worked with Tibetan refugees. In 1983, six years after her first major retrospective in Bonn, a stroke forced her to return to Germany. Permanently. She died in 1985, at her sister's home in Wetzlar, Hesse – surprisingly unspectacularly for an artist who had travelled the world.

(1) Krull, Germaine: Chien-fou. 1934 – Ceux de Brazzaville. 1944 – Click entre deux guerres. 1976 – La vie mène la danse. 1982. All manuscripts are from the archives of Germaine Krull at Museum Folkwang, Essen. »La vie mène la danse« was published as »La vita conduce la danza«, Florenz 1992 and »Click entre deux guerres« was partially translated into German and published in: Honnef, Klaus (1977): Germaine Krull. Fotografien 1922-1966. Ausstellungskatalog Bonn, S. 117-190. Unless otherwise noted all further quotations are from this text as well as from: Sichel, Kim (1999): Avantgarde als Abenteuer. Leben und Werk der Photographin Germaine Krull. München.

(2) Rueckert, Ulrike (2007): »Die Fotografie ist ein schöner Beruf«: Das schillernde Leben der Germaine Krull. München. Bayerischer Rundfunk – Dumas, Marie Hélène (2009): Lumières d'exil. Paris

(Text from 2012; translated with DeepL.com; edited by Ramona Fararo, 2025.

Please consult the German version for additional information, pictures, sources, videos, and bibliography.)

Author: Annette Bußmann

Quotes

QUOTES BY KRULL

Photography is a beautiful, creative profession and the photographer an artist – if he is able to feel the image. [Krull (1977), p. 190]

Perhaps these metal giants, in whose presence I felt very small and insignificant, inspired fear in me; but an irresistible desire to capture them in an image, to bring them closer and thereby perhaps make them more human, compelled me to photograph them. [Krull quoted in Sichel (1998), p. 71/72]

The photographer's first skill is knowing how to look. You look with your eyes. The same world, seen with different eyes, is not exactly the same. It is the world, seen through a personality. With a click of the shutter, the lens registers the world from the outside and the photographer from the inside. [Krull quoted by Sichel (1998), p. 83]

QUOTES ABOUT KRULL

I can easily imagine Krull in her studio, cigarette between her lips, the smoke drifting into her eyes… The children of misfortune push, shove, complain, argue and rush around Krull and her lens, round like a polyp's eye, to line up in front of the camera… Later (...) one seeks a name from our familiar vocabulary for these objects, aggressive in their naked reality. [Marc Orlan (sic! – i.e. Pierre Mac Orlan) around 1928, quoted in Krull (1977), p. 124]

When photography breaks away from contexts such as those provided by a Sander, a Germaine Krull, or a Bloßfeldt, when it emancipates itself from its physiognomic, political, and scientific interest, it becomes 'creative.' [Walter Benjamin (1935/1993), A Little History of Photography, p. 62]

They are like a mirror that transforms the image of the world; you and your camera are creating a new world, one that has left all things mechanical behind and found its soul. [Jean Cocteau in a letter to Germaine Krull 04/1930, quoted in Krull (1977), p. 140]

Is photography an art? The Dutch artist Germaine Krull, one of the most outstanding representatives of art photography of our time, would say no… Let's hear what the great artist has to say: 'The photographer always remains grounded in reality'... Germaine Krull fights against conventional photography… She wants to achieve the originality and independence with which she wants to pursue her artistic craft only through progressive working methods and technical improvements. She never cheats. [Frédéric Lefèvre (1930), quoted in Krull (1977), p. 125]

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.