Biography • Weblinks • Literature & Sources

Biography

INTRODUCTION

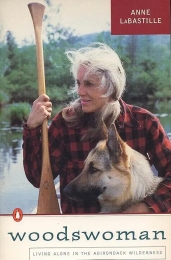

“Woodswoman.” This is the first word in the titles of a series of four of Anne LaBastille’s many books. It encapsulates her lifelong desire, as a woman in the second half of the 20th century, to live and work on her own, as close to nature – especially wildlife in woods/wilderness – as she could. In her first book in this series, titled simply Woodswoman (1976 – later Woodswoman i), she recalled, “I sought peace and solitude and I found them both, in nature. In the wilderness, I rediscovered a clarity and purpose I had lost in the city.”

Even as a child, LaBastille felt drawn to nature, spending as much time there as possible wherever she could find woodsy areas in and around suburban Montclair, New Jersey. She did not receive much support from her parents. Her mother in particular disapproved of her dressing like a boy and her eagerness to go camping in the woods, admonishing her with such directives as “girls don’t do that!”

But LaBastille followed her dream. After high school she moved to Florida and studied marine biology for two years at the University of Miami, finding jobs as a nature guide in wild places such as the Everglades. In 1955 she graduated from Cornell University with a B.S. degree in Conservation of Natural Resources. Encouraged to go on for advanced degrees, she later earned an M.S. degree from Colorado State University in Wildlife Management in 1961, and a Ph.D. degree in Wildlife Ecology from Cornell in 1969.

While she was still in college, LaBastille got a summer job performing a variety of tasks at the Covewood Lodge in the town of Eagle Bay on Big Moose Lake in the Adirondack Mountains in northern New York state. During her time there, she and the owner of the lodge, C.V. “Major” Bowes, became close; they were married in 1964 and stayed together for seven years, then finally divorced. LaBastille’s primary goal was to become an international ecological consultant. She found a good place to pursue it, at first in the Adirondacks and eventually in many countries around the world. She was a prolific writer of both scientific and popular works, including some for children; according to her obituary in the New York Times, “she wrote 16 books, more than 150 articles for magazines … and over two dozen scientific papers.” She was also an expert photographer, as well as a teacher, lecturer, and leader of expeditions into nature. She was widely admired and won many honors for her work.

During one harsh winter in the mid-1960s, seeking escape from the cold and snow of the Adirondacks, LaBastille made a trip south to Lake Atitlán in Guatemala with her then husband, who was also keen on nature study and was already familiar with that area. This trip helped her formulate her lifetime goal of studying nature internationally. But she also very much wanted to continue living for most of the year in the Adirondacks. However, after her divorce, she could no longer live at Covewood; she had to find a home of her own. She was able to acquire some property – 22 acres – and, inspired by the nineteenth-century American naturalist Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden, she designed and built (almost completely by herself, with some help from a pair of strong local men) a small cabin near a lake, hidden in the woods several miles from human traffic and distraction. The cabin, which she named West of the Wind, was 12 feet by 12 feet and had no electricity or indoor plumbing or telephone.

A few years later LaBastille, realizing she needed even more privacy, built a second, even smaller cabin, even further removed from the trappings of modern life. She named this cabin Thoreau ii. There she could explore nature first hand, its deep woods and nearby lakes – most often accompanied by one or two of a series of her beloved German shepherd dogs – and write about the wildlife there with a minimum of interruption. She wrote numerous books (including a few for children) and many articles, both popular and scientific. Much of her work appeared in such prestigious journals as The National Geographic, International Wildlife, and more.

Thus LaBastille began an annual pattern of living in her cabins, exploring nature and writing on her own during the warm months of the year, and traveling frequently to warmer climes in the winter – Guatemala, other countries in Central America, the Caribbean, South America, and elsewhere. There she undertook ecological studies of natural surroundings, always with a view toward conserving nature and understanding the relationship between the human and non-human worlds. LaBastille was especially fond of visiting and studying aspects of nature in Guatemala, which she visited many times, getting to know and befriend some of the local people and learning their language (Spanish, and to a lesser extent, Mayan), and involving some of them in her research. She was enchanted by the local flora and fauna, so different from those of the forested mountains and many lakes of the Adirondacks. She never lost her love for and dedication to both environments. In a period when global warming was increasing, and acid rain and pollution were more and more threatening wild areas in many places around the world, pushing growing numbers of species of plants and animals toward extinction, LaBastille fought against those trends in a lifelong effort to stop them.

Unfortunately, although LaBastille had many supporters and some of her books were very popular, not everyone agreed with her outlook on nature and her efforts to conserve it. As she grew older, she found herself increasingly a target of people who lacked her passion for maintaining the natural environment, as they cut down trees indiscriminately to build expensive vacation homes and raced up and down wild, tranquil lakes without concern for how they were affecting animal and plant inhabitants. Finally she had to move out of her cabins. She was able to purchase a farm in Westport, NY, near Lake Champlain. In 1993 a barn on her property was mysteriously burned down; authorities concluded the fire was the result of arson. In addition, in her seventies her health began to fail. Eventually she developed Alzheimer’s disease, and had to move into a care facility in Plattsburgh, New York. She died there in 2011 at the age of 77.

A FEW SELECTED BOOKS BY ANNE LABASTILLE

Woodswoman (later referred to as Woodswoman i) – LaBastille is perhaps best known for her series of four Woodswoman books, the first one published in 1976, the following two at ten-year intervals, and the fourth book five years later. This first book of the four, complete with maps and diagrams as well as many photographs that she took, includes numerous lyrical passages expressing her love for and feeling of intimacy with virtually all aspects of the natural world around her, including trees, as the seasons passed; although in one or two sections, she reports on more annoying – though sometimes comic – aspects of her new lifestyle, such as returning home late one evening to find her kitchen overtaken and left in disarray by an invading raccoon mother and her four kits. LaBastille reveals her own increasing imperative to convince other people of the need to conserve nature against numerous increasing threats to it. She also expresses her own personal belief that as a woman in this endeavor, she can do as well as a man, although she welcomes the company and support of men who think and feel as she does.

Always willing and eager to share her enchantment with nature with others similarly inclined, LaBastille became an Adirondack Park Guide in the 1970s and retained the position for many years, providing guide services for backpacking and canoe trips in the Adirondack mountains. Her enthusiasm, and her many opportunities to observe nature so closely, shine through much of her writing. In a typical passage, she writes of the coming of Spring after a long hard Adirondack winter as she looks out on Black Bear Lake: “A flute pipes…. a White-throated Sparrow is throwing his heart into a love song for an as yet unfound mate. His liquid whistle, translated by unromantics as ‘Sam Pea-bo-dy,’ is one of the most beautiful sounds of the Adirondacks .…. The ‘flute of the woods’ is followed by the effervescent trilling of a Winter Wren. Size for size, this miniature member of the bird world belts out a louder, longer song than any other species I know. He, too, is guarding his bit of balsam woods and advertising for a teeny female wren to join him.”

Near the end of the first book in her Woodswoman series, in a passage often quoted by reviewers, LaBastille (after a work-related stint of living in Washington DC for several months) compares her feelings about living in the city vs. living in nature:

“Still the cabin is the wellspring, the source, the hub of my existence. It gives me tranquility, a closeness to nature and wildlife, good health and fitness, a sense of security, the opportunity for resourcefulness, reflection, and creative thinking. Yet my existence here has not been, and never will be, idyllic. Nature is too demanding for that. It requires a constant response to the environment. I must adapt to its changes – the seasons, the vagaries of weather, wear and tear on house and land, the physical demands on my body, the sensuous pulls on my senses. Despite these demands, I share a feeling of continuity, contentment, and oneness with the natural world, with life itself, in my surroundings of tall pines, clear lakes, flying squirrels, trailless peaks, shy deer, clean air, bullfrogs, black flies, and trilliums.” Her words and deeds have inspired many to follow her path.

Mama Poc: An Ecologist’s Account of the Extinction of a Species – In 1964, during a trip to Guatemala, LaBastille learned of a particular bird, (Podilymbus gigas), also known as the giant grebe or giant pied-billed grebe (“pied” means “striped,” referring to the stripe on the bird’s beak), found only in and around a volcanic lake, Lake Atitlán, in southwestern Guatemala. This species, which was flightless (its wings being too short for it to fly), was related to a much smaller grebe found in numerous other areas. From her research, LaBastille learned that naturalists who several decades earlier had counted the larger grebes in Lake Atitlán, had reported more than 200 of them. However, when LaBastille, with the help of local friends, made her own count in 1965, they found only slightly more than 80. What could have caused such a drastic reduction?

LaBastille was determined to find out. (Because of her keen interest in the problem, local people dubbed her “Mama Poc,” “poc” being a sound similar to the birds’ call.) At first, suspicion fell on harvesters of a species of reeds that grew along much of the lake’s edge, since that was where the large grebes built their nests. But local Guatemalans had been involved for centuries in harvesting these reeds to weave and make into furniture, as they lacked sufficient wood that they might have used instead. Could such harvesters be the culprit? Or possibly poachers?

Finally LaBastille learned that in 1958 and 1960, Pan American Airlines had stocked Lake Atitlán with large mouth bass to encourage wealthy sports fishermen from other countries to come take advantage. The bass, in turn, fed on small fish that the large grebes also fed on, as well as on grebe chicks. In 1966, LaBastille helped establish a refuge for the big grebes, in a shallow bay that workers walled off from the rest of the lake. Many local people supported and publicized her efforts enthusiastically. By 1973 the grebe population in the refuge had risen to 2010. But three years later, in 1976, a powerful earthquake fractured the Lake Atitlán bed, leading to a severe drop in the lake’s water level and to a count in 1983 of only 32 grebes, some of which were suspected to be hybrids with the smaller grebe species.

Much to LaBastille’s sorrow, Podilymbus gigas was declared officially extinct in 1990. LaBastille tells a version of this story in an article in a popular journal, “The Giant Grebes of Atitlán: A Chronicle of Extinction,” published in 1992 (see full citation below). Also cited below is LaBastille’s earlier, much longer, more technical account of the story. Both of these works are available online.

Women and Wilderness: Women in Wilderness Professions and Lifestyles – Unusually for LaBastille, and unlike her other books, this one is a historical work. The first part of the book is an overview of women’s attitudes toward and relationship with nature and its conservation in the American west in frontier times and more recent times, based on letters and diary entries. LaBastille documents women’s various reasons for and feelings about “going west” into the wilderness, often with their husbands and children, and how they coped with unfamiliar, often dangerous surroundings.

The remaining part of this book features LaBastille’s individual, several-page accounts of the contributions of fifteen American women ecologists (not including herself) during the 20th century, who have worked in the field of nature conservation. Included, for example, are Margaret (“Mardy”) Murie (1902-2001), who, with her naturalist husband Olas Murie, helped create the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; Carol Ruckdeschel (b. 1941), who helped establish the Cumberland Island National Seashore in the US state of Georgia; and Nicole Duplaix (b. 1943), who worked extensively in Suriname in South America to help preserve that country’s endangered otters. Two appendices in the book include a questionnaire that LaBastille designed to help readers assess their own likelihood of becoming successful woodswomen, and a list of schools and other institutions that offer training in how to do so.

Gemara Gifford, a graduate student at Cornell in the field of natural resources, summing up LaBastille’s influence, has observed, “I think her greatest legacy is to the women in natural resources and conservation. I see a lot of aspects of what I’m trying to do in the work she did, and know that I probably wouldn’t be here if she hadn’t paved the way for women.” – quoted in the Cornell Chronicle, 2015

Author: Dorian Brooks

Links

SOME ONLINE SOURCES

Wildlife Monographs, Aug. 1974, No. 37, pp. 3-66. LaBastille, Anne, “Ecology and Management of the Atitlán Grebe, Lake Atitlán, Guatemala”

“The Giant Grebes of Atitlán: a Chronicle of Extinction,” Winter 1992, pp. 11-15. LaBastille, Anne.

(Put title in google) Anne LaBastille, https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/labastille-1992-grebe.pdf

Wikipedia, “Anne LaBastille”

“Anne LaBastille: Remembering the Legendary Woodswoman”

By Adirondack Explorer

August 22, 2011

Literature & Sources

BOOKS CONSULTED

Woodswoman (later known as Woodswoman i.) LaBastille, Anne. E. P. Dutton, New York, 1976

Assignment: Wildlife. LaBastille, Anne. E. P. Dutton, New York, 1980

Women and Wilderness: Women in Wilderness Professions and Lifestyles. LaBastille, Anne. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, 1980

Beyond Black Bear Lake (later known as Woodswoman ii). LaBastille, Anne. W. W. Norton, New York, 1987

Mama Poc. An Ecologist's Account of the Extinction of a Species. LaBastille, Anne. W. W. Norton, New York, 1990

Woodswoman iii. Book Three of the Woodswoman's Adventures. LaBastille, Anne. West of the Wind Publications, Westport, N.Y., 1997

Jaguar Totem: The Woodswoman Explores New Wildlands and Wildlife. LaBastille, Anne. West of the Wind Publications, Westport, N.Y. 1999

Woodswoman iiii. Book Four of the Woodswoman's Adventures. LaBastille, Anne. West of the Wind Publications, Westport, N.Y. 2003

American Women Conservationists: Twelve Profiles. Chapter 7, “Contemporary Women Conservationists” (includes a section on Anne LaBastille). Holmes, Madelyn. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004.

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.