Fembio Specials Women from North and South Tyrol and the Trentino Anna Stainer-Knittel

Fembio Special: Women from North and South Tyrol and the Trentino

Anna Stainer-Knittel

(Maria Anna Rosa Knittel [Geburtsname]; Anna Stainer; Anna Knittel)

Born 28 July 1841 in Elbigenalp in the Lech Valley, Austria

Died 28 February 1915 in Wattens, Austria

Austrian painter from North Tyrol, the original “Geierwally” (“Eagle Wally”)

Biography

Biography

What Andreas Hofer is for the Tyrolese among men, “Geierwally” is among women – a role model, a female with qualities usually associated with only the best men of this Alpine folk, an unyielding figure who defies even the mountain spirits, the “Murzoll” and his daughters, the “saligen Fräuleins” (Blessed Maidens). And – precisely because she is a woman and not a man – she commands respect and even seems dangerous.

As is often the case, the evolution of her heroic image reflects a long-since inspeparable combination of reality and fiction. But in fact the “real” Geierwally, Anna Stainer Knittel from the Lech Valley, was a woman who wouldn’t have needed to be mythologized: Perhaps she became a legend because she lived her life with great intentionality, independence and great determination. She had no fear of the forces of nature that often intimidate inhabitants of the mountains.

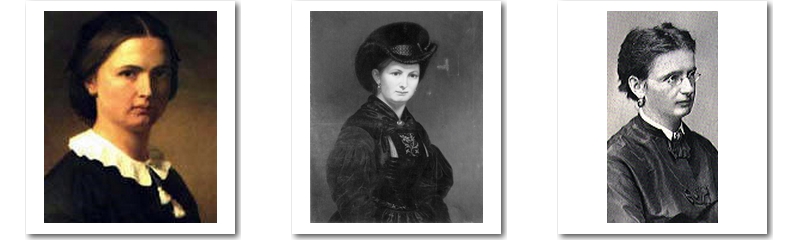

Anna Knittel was born on July 28th, 1841 in Elbigenalp in the Lech Valley, the daughter of a gunsmith and a grand-niece of the then famous painter Joseph Anton Koch. Her often barbed but accurate caricatures of her classmates revealed early that she too had talent in drawing.

She first became famous, however, through a “test of courage,” which was so successful that she performed it twice:

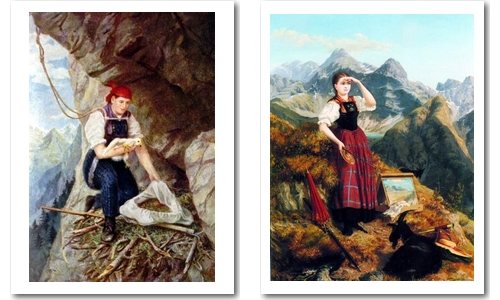

In an age when eagles (then derogatorily called “vultures”) were pursued because they preyed upon young lambs, she slipped without hesitation into her brother’s Lederhosen and roped herself down a steep rock face to clear out an eagle’s eyrie. Not a single man from the village had been ready to attempt this perilous deed, and her brother had dangled from the rope for seven hours once already and was not inclined to do it a second time. So she took on the challenge of grabbing the young eagles, raising them and later selling them at a fair. All this was an undertaking that one would hardly have expected of a woman in the year 1863.

Shortly thereafter the Bavarian travel-writer Ludwig von Steub embedded the heroic deed in a literary narrative, and the lyric poet Anton Renk named Anna Knittel “Brunhilde of the Lech Valley.”

When finally – 12 years after the event itself – the novel “Die Geierwally” appeared, no theatrical piece, no film could undo how the popular author Wihelmine von Hillern had reshaped her story: Anna had become a Walburga, the daughter of a gunsmith was turned into a farmer’s daughter, and the Lech Valley transformed to the legend-rich Ötz Valley.

Admittedly, Anna Knittel had done a bit of advertising of her own when she displayed a painting of herself raiding the eagles’ nest in the show-window of her souvenir shop. The author Wilhelmine von Hillern had seen this picture as she passed by and was immediately captivated. For “Geierwally” was a kind of personal emancipation for von Hillern: through it she could distance herself from her mother, the successful popular author Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, and liberate herself as well from a society which had forced her to conceal a child she had had outside of marriage.

“She’s the strongest and most beautiful girl in Tyrol,” said the mountain goat hunter, “but prickly as a wild cat – it’s shameful, how she chases the boys home. Of course, it’s not her fault: her father used to beat her terribly and raised her like a boy.” (Wilhelmine von Hillern, Die Geierwally)

When Anna Knittel raided the eagle’s roost in 1863 she was already a student in Munich and had decided against the typical feminine path for herself. Once she had demonstrated her artistic talent as a child and it was confirmed by various experts, she was able to assert herself and move away to Munich.

She most likely did not attend the state academy of art, since it was not open to women before 1920, but attended a private academic preparatory art school “as the very first female among a crop of men,” as she proudly noted in her diary.

When – after her return – things became too limiting for her in the Lech Valley, and the Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum purchased a self-portrait from her (wearing Tyrolean costume), she quickly moved to Innsbruck, where she could earn her own money. And that she would continue to do for the rest of her life, even as the mother of four children. She married the plaster cast maker (Gipsformator) Engelbert Stainer against her father’s wishes; Stainer had an extra-marital child to support as well.

She became famous above all for her oil landscapes and floral paintings; they were practically grabbed from her hands by eager tourists. But by her own account she also painted upwards of 130 portraits, among them: Archduke Karl Ludwig, Field Marshall Radetzky and Emperor Franz Joseph I. She always signed her paintings with her maiden name. Once photography took over the field of portraiture she developed her specialty in flower-paintings, which she continued to produce up to her death, and otherwise concentrated her energy on her drawing school for girls. She caused a stir when she had her hair cut short.

In 1873 Anna Stainer Knittel was represented at the Vienna World’s Fair with her oil painting “Alpenblumenkranz” (Alpine Flower Wreath). It was sold to an English buyer for 40 pounds sterling. She died on February 28th, 1915 in the house of her son, Dr. Karl Stainer, in Wattens, following an incompletely healed case of pneumonia.

“And the Tyrolean continued telling the stranger: that figure of a girl that stands out up there against the sky is called Walburga Strommingerin, but they also call her Geierwally.

And truly, she deserved this name: For her courage and strength were limitless – as though she had the wings of an eagle. Her mind was rugged and inaccessible, like the sharp-edged rocky peaks where the eagles nest and tear apart the clouds of the sky.” (Wilhelmine von Hillern, Die Geierwally)

Anna Stainer Knittel was immortalized in the figure of Geierwally; the material of the novel was adapted countless times for the theater, and the novel itself was translated into eleven languages and filmed five times, for example as a naturalistic Blut- und Boden-story, a Nazi propaganda film with all the inhabitants of the village of Längenfeld and Heidemarie Hatheyer, a discovery of Luis Trenker.

As the operatic heroine “La Wally” the wild woman of Tyrol provided the composer Alfredo Catalani (a contemporary of Puccini) with his only real triumph. As befits the genre, Wally is not happily united with her lover at the end of the opera; rather, when he is hurled into the depths by an avalanche, she follows him with a leap to her own death.

The most famous aria from Catalani’s opera was recycled in almost 20 movies as film music, and it plays a central role in the French cult-film “Diva” by Beinix (1981). Tyrolean tourist advertising also has long made use of the the wild Geierwally: She overcomes the fear that has always caused inhabitants of such regions to represent and conjure up survival through all sorts of myths. And even though myth and fiction soon covered over real life, they have nonetheless kept the memory of Anna Knittel, the original Geierwally, alive.

trans. Joey Horsley

For additional information please consult the German version.

Author: Astrid Kofler

If you hold the rights to one or more of the images on this page and object to its/their appearance here, please contact Fembio.